Home --> Health Equity Lens --> Current Efforts

|

|

Current Efforts

|

|

Despite a research focus on health inequities since the 1970s and growing attention to SDOH in public health practice, health inequities remain a large, persistent problem that has garnered the attention of many state and federal agencies, foundations, and non-profit organizations. Over the past two decades, federal agencies have released numerous reports regarding health disparities, and have offered recommendations for addressing them. Those recommendations have become increasingly focused on the SDOH.

The contents of three key national level reports: Healthy People 2020, the National Stakeholder Strategy, and the Department of Health and Human Services’ Action Plan to Reduce Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, as well as Delaware Division of Public Health’s Health Equity Strategy are particularly relevant to this guide and influenced its development. Furthermore, the measures taken by the Affordable Care Act to promote health equity initiatives nationally and in Delaware specifically are also summarized below.

The contents of three key national level reports: Healthy People 2020, the National Stakeholder Strategy, and the Department of Health and Human Services’ Action Plan to Reduce Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, as well as Delaware Division of Public Health’s Health Equity Strategy are particularly relevant to this guide and influenced its development. Furthermore, the measures taken by the Affordable Care Act to promote health equity initiatives nationally and in Delaware specifically are also summarized below.

National Efforts to Advance Health Equity

1. Healthy People 2020

The Healthy People initiative provides science-based 10-year national objectives for improving the health of all Americans. Each 10-year plan is developed through a multi-year process that includes input from a wide range of experts and stakeholders. In its third iteration, Healthy People 2020, released in December of 2010, articulates a framework for achieving its national goals and objectives through a foundation in the determinants of health. As mentioned earlier, Healthy People 2020 distinguishes between social and physical determinants in the environment, but recognizes their interrelated nature, as they both contribute to the places where people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age. Healthy People 2020 refers to the social and physical determinants collectively as "societal determinants of health." This phrase captures the interrelated and complex nature of the social and physical determinants.

Importantly, Healthy People 2020 recognizes that the social environment is very broad and reflects things like culture, language, political and religious beliefs, and social norms and attitudes. The social environment also encompasses socioeconomic conditions (i.e. poverty) and community characteristics (i.e. exposure to crime and violence), as well as the degree and quality of social interactions. According to the Secretary’s Advisory Committee, mass media and emerging communication and information technologies, such as the Internet and cellular telephone technology, are ubiquitous elements of the social environment that can affect health and well-being. Furthermore, policies in settings such as schools, workplaces, businesses, places of worship, health care settings, and other public places are part of the social environment. Economic policy is highlighted as a critically important component of the social environment.

According to Healthy People 2020, the physical environment consists of the natural environment (i.e., plants, atmosphere, weather, and topography) and the built environment (i.e., buildings, spaces, transportation systems, and products that are created or modified by people). The physical environment affects health directly, such as through physical hazards like air pollution, and indirectly, such as the way in which the environment encourages or discourages physical activity. The Secretary’s Advisory Committee suggests that interventions should promote environmental justice by eliminating disparities in exposure to harmful environmental factors and improving access to beneficial ones.

Given the range of factors in the social and physical environment affecting health, Healthy People 2020 calls for a multi-sector approach to address health equity. The Secretary’s Advisory Committee notes that the 10-year goals and objectives “can be achieved only if many sectors of our society—such as transportation, housing, agriculture, commerce, and education, in addition to medical care—become broadly and deeply engaged in promoting health.” The Committee acknowledges that many agencies do not have a mandate to address these cross-cutting issues, and recommends that the public health community provide leadership and encourage collaboration to promote health in the social and physical environment.

Importantly, Healthy People 2020 recognizes that the social environment is very broad and reflects things like culture, language, political and religious beliefs, and social norms and attitudes. The social environment also encompasses socioeconomic conditions (i.e. poverty) and community characteristics (i.e. exposure to crime and violence), as well as the degree and quality of social interactions. According to the Secretary’s Advisory Committee, mass media and emerging communication and information technologies, such as the Internet and cellular telephone technology, are ubiquitous elements of the social environment that can affect health and well-being. Furthermore, policies in settings such as schools, workplaces, businesses, places of worship, health care settings, and other public places are part of the social environment. Economic policy is highlighted as a critically important component of the social environment.

According to Healthy People 2020, the physical environment consists of the natural environment (i.e., plants, atmosphere, weather, and topography) and the built environment (i.e., buildings, spaces, transportation systems, and products that are created or modified by people). The physical environment affects health directly, such as through physical hazards like air pollution, and indirectly, such as the way in which the environment encourages or discourages physical activity. The Secretary’s Advisory Committee suggests that interventions should promote environmental justice by eliminating disparities in exposure to harmful environmental factors and improving access to beneficial ones.

Given the range of factors in the social and physical environment affecting health, Healthy People 2020 calls for a multi-sector approach to address health equity. The Secretary’s Advisory Committee notes that the 10-year goals and objectives “can be achieved only if many sectors of our society—such as transportation, housing, agriculture, commerce, and education, in addition to medical care—become broadly and deeply engaged in promoting health.” The Committee acknowledges that many agencies do not have a mandate to address these cross-cutting issues, and recommends that the public health community provide leadership and encourage collaboration to promote health in the social and physical environment.

*Include Table 1 (p.29)

Finally, the Secretary’s Advisory Committee calls for more research regarding the societal determinants of health and efforts to address them. The Committee argues that the availability of high quality data for all communities should be a priority for public health departments and clinical preventive research. Furthermore, it acknowledges the need to build the evidence for community-based interventions and recommend that HHS place more attention on examining policies that impact the social and physical environment. Finally, the Committee stresses the importance of community-based participatory research. Elements of these recommendations are included in Sections 6 (Policy-Oriented Strategies) and 7 (Data, Research, and Evaluation for Health Equity).

Finally, the Secretary’s Advisory Committee calls for more research regarding the societal determinants of health and efforts to address them. The Committee argues that the availability of high quality data for all communities should be a priority for public health departments and clinical preventive research. Furthermore, it acknowledges the need to build the evidence for community-based interventions and recommend that HHS place more attention on examining policies that impact the social and physical environment. Finally, the Committee stresses the importance of community-based participatory research. Elements of these recommendations are included in Sections 6 (Policy-Oriented Strategies) and 7 (Data, Research, and Evaluation for Health Equity).

Spotlight: Health in All Policies (HiAP)

One recommendation for addressing societal determinants of health across sectors is for government to adopt a “Health in All Policies” (HiAP) approach. A HiAP approach requires intersectoral partnerships at all government levels and with non-traditional partners, with a focus on social and environmental justice, human rights, and equity. A HiAP approach has the potential to make meaningful impact in achieving health equity. An in-depth discussion of this approach, including related tools and strategies, is included in Section 6 of the guide.

The Secretary’s Advisory Committee acknowledges that individual/disease-specific and population-based perspectives are both necessary to achieve optimal health for all. Rather than choose one or the other, they should be viewed (and used) as two components of an integrated solution. Table 1, excerpted from the Report of the Secretary’s Advisory Committee, provides examples of the two approaches and highlights their advantages and disadvantages from both a policy perspective and a practical perspective.

The Secretary’s Advisory Committee acknowledges that individual/disease-specific and population-based perspectives are both necessary to achieve optimal health for all. Rather than choose one or the other, they should be viewed (and used) as two components of an integrated solution. Table 1, excerpted from the Report of the Secretary’s Advisory Committee, provides examples of the two approaches and highlights their advantages and disadvantages from both a policy perspective and a practical perspective.

2. The National Stakeholder Strategy for Achieving Health Equity (NSS)

In response to persistent health inequities in the United States and a call to action for a national, comprehensive, and coordinated effort to eliminate disparities, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services' Office of Minority Health established The National Partnership for Action to End Health Disparities (NPA). The NPA was created with the support of nearly 2,000 attendees of the National Leadership Summit for Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health. Sponsored by the Office of Minority Health, the Summit provided a forum to strategize how to eliminate health disparities by increasing the effectiveness of programs that target health disparities and fostering effective coordination of partners, leaders, and other stakeholders.

|

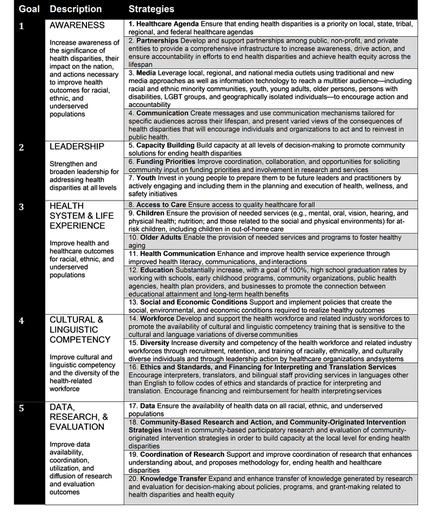

In 2011, the NPA released the National Stakeholder Strategy for Achieving Health Equity (NSS), which was developed through a very collaborative process, including contributions from thousands of individuals representing government, non-profit organizations, academia, business, and the general public. When the NPA released the initial draft for comment, thousands of community members responded. The resulting report is described as a “roadmap” for stakeholders at local, state, and regional levels to eliminate health disparities. The main values of the NSS are community engagement, community partnerships, cultural and linguistic literacy, and non-discrimination. The NSS report includes a set of five overarching goals and 20 community-driven strategies to help achieve them. Table 2 (shown right), excerpted from the NSS, outlines these goals and strategies. For each of the 20 strategies, the report provides a menu of objectives, measures, and potential data sources as tools for stakeholders to use in implementing any given strategy. The strategies are intended to be translated and operationalized at different geographic levels (e.g. local, state, and regional) and across sectors. The NPA acknowledges many challenges in accomplishing these tasks and offers the report as a forum for lessons learned, best practices in the field, and tracking progress. |

3. The HHS Action Plan to Reduce Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Action Plan to Reduce Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities was released simultaneously with the NSS. It represents the federal commitment to achieving health equity and the HHS response to the strategies recommended in the NSS. The Action Plan also builds on Healthy People 2020 and leverages other federal initiatives (e.g. the National HIV/AIDS Strategy, the First Lady’s Let’s Move initiative, etc.) and many provisions of the Affordable Care Act. It outlines specific goals and related actions that HHS agencies will take to reduce health disparities among racial and ethnic minorities in the following five areas:

- Transforming health care by expanding insurance coverage, increasing access to care, and fostering quality initiatives;

- Strengthening the health workforce to promote better medical interpreting and translation services and increased use of community health workers;

- Advancing the health, safety, and well-being of Americans by promoting healthy behaviors and strengthening community-based programs to prevent disease and injury;

- Advancing knowledge and innovation through new data collection and research strategies; and

- Increasing the ability of HHS to address health disparities in an efficient, transparent, and accountable manner.

4. The Affordable Care Act and Incentives for Investing in Community Health

Poor performance of the health care system—including excessive and potentially unnecessary spending, inadequate access to care, and poor or uneven quality of care—have driven reform efforts for decades. The Affordable Care Act (ACA), passed in 2010, aims to reduce costs, increase access, and improve quality of care. Embedded in many provisions of the ACA are opportunities to address social determinants of health and reduce health inequities, particularly through investments in community health.

Increased awareness and understanding of how the social and physical environments impact health and health inequities is occurring at a time when the nation’s health care system is undergoing immense change. The current health care landscape, including the passage of the ACA and promotion of the “Triple Aim,” has created new opportunities and incentives for health care providers to pay more attention to the SDOH.

The Triple Aim is a framework originally developed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. It aims to optimize health system performance. The framework draws attention to three interrelated goals that are meant to be pursued simultaneously:

Many public and private health care providers have adopted this approach, which is supported and reinforced through various ACA provisions. The ACA’s expansion of health insurance for low- and moderate-income individuals reduces the financial barrier to accessing primary care for millions of individuals. This also gives providers the opportunity to address patient care in a more holistic and prevention-oriented manner rather than the episodic or urgent care that is more typical among those without adequate health insurance. Additionally, new models of care have emerged which enhance patient care through improved care coordination, and allow real-time linkage of patients to local social service agencies and related services. One such model is the patient-centered medical home (PCMH).

The ACA’s expansion of health insurance may also create new opportunities for hospital community benefit programs. According to a recent study, most non-profit hospitals, which are required to dedicate a portion of their revenue to provide community benefits, have done so in the form of discounted or uncompensated care for uninsured or under-insured individuals (Young et al., 2013). With fewer uninsured individuals, hospitals may now use their Community Benefit Programs for community-oriented prevention efforts. Similarly, the ACA now requires tax-exempt hospitals to regularly conduct community health needs assessments and to develop plans to address those needs (Young et al., 2013). This offers further incentive for hospitals to use community benefit programs to address upstream community needs and work to improve population health.

According to a recent report by the Commonwealth Fund (Bachrach et al., 2014), specific payment reform efforts, such as value-based purchasing and outcomes-based payment models, provide new economic incentives for providers to address patients’ social needs. For instance, Medicare’s Hospital Readmission and Reduction Program, created through the ACA, gives hospitals financial incentives to avoid readmissions by reducing payments to those hospitals where patients with certain medical conditions readmit within 30 days of their prior discharge. Although readmissions may be linked to health care quality, evidence also demonstrates a link between social factors and risk of readmissions. Other payment mechanisms that promote managing care, such as capitated, global, and bundled payments, also provide an incentive for providers to address patients’ unmet social needs, which helps improve health outcomes. This is in contrast to traditional fee-for-service models that theoretically incentivize the quantity of services versus the quality of care.

The Commonwealth Fund report also highlights indirect economic benefits of health care providers investing in social interventions in the form of increased employee productivity, provider satisfaction, and patient satisfaction (Bachrach et al., 2014). Strategies that address patients’ social needs free up physicians and other health care providers to address more immediate physical needs and increase their time spent providing direct medical care to patients. Since providers can bill for the time spent with the patient, this increases provider income and promotes provider satisfaction, as they believe they are providing higher quality care. Higher quality care, in turn, translates into higher patient satisfaction.

Increased awareness and understanding of how the social and physical environments impact health and health inequities is occurring at a time when the nation’s health care system is undergoing immense change. The current health care landscape, including the passage of the ACA and promotion of the “Triple Aim,” has created new opportunities and incentives for health care providers to pay more attention to the SDOH.

The Triple Aim is a framework originally developed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. It aims to optimize health system performance. The framework draws attention to three interrelated goals that are meant to be pursued simultaneously:

- Improving the patient experience of care (including quality and patient satisfaction)

- Improving the health of populations

- Reducing the per capita cost of health care

Many public and private health care providers have adopted this approach, which is supported and reinforced through various ACA provisions. The ACA’s expansion of health insurance for low- and moderate-income individuals reduces the financial barrier to accessing primary care for millions of individuals. This also gives providers the opportunity to address patient care in a more holistic and prevention-oriented manner rather than the episodic or urgent care that is more typical among those without adequate health insurance. Additionally, new models of care have emerged which enhance patient care through improved care coordination, and allow real-time linkage of patients to local social service agencies and related services. One such model is the patient-centered medical home (PCMH).

The ACA’s expansion of health insurance may also create new opportunities for hospital community benefit programs. According to a recent study, most non-profit hospitals, which are required to dedicate a portion of their revenue to provide community benefits, have done so in the form of discounted or uncompensated care for uninsured or under-insured individuals (Young et al., 2013). With fewer uninsured individuals, hospitals may now use their Community Benefit Programs for community-oriented prevention efforts. Similarly, the ACA now requires tax-exempt hospitals to regularly conduct community health needs assessments and to develop plans to address those needs (Young et al., 2013). This offers further incentive for hospitals to use community benefit programs to address upstream community needs and work to improve population health.

According to a recent report by the Commonwealth Fund (Bachrach et al., 2014), specific payment reform efforts, such as value-based purchasing and outcomes-based payment models, provide new economic incentives for providers to address patients’ social needs. For instance, Medicare’s Hospital Readmission and Reduction Program, created through the ACA, gives hospitals financial incentives to avoid readmissions by reducing payments to those hospitals where patients with certain medical conditions readmit within 30 days of their prior discharge. Although readmissions may be linked to health care quality, evidence also demonstrates a link between social factors and risk of readmissions. Other payment mechanisms that promote managing care, such as capitated, global, and bundled payments, also provide an incentive for providers to address patients’ unmet social needs, which helps improve health outcomes. This is in contrast to traditional fee-for-service models that theoretically incentivize the quantity of services versus the quality of care.

The Commonwealth Fund report also highlights indirect economic benefits of health care providers investing in social interventions in the form of increased employee productivity, provider satisfaction, and patient satisfaction (Bachrach et al., 2014). Strategies that address patients’ social needs free up physicians and other health care providers to address more immediate physical needs and increase their time spent providing direct medical care to patients. Since providers can bill for the time spent with the patient, this increases provider income and promotes provider satisfaction, as they believe they are providing higher quality care. Higher quality care, in turn, translates into higher patient satisfaction.

Health Equity Initiatives in Delaware

1. Delaware Division of Public Health's Health Equity Strategy

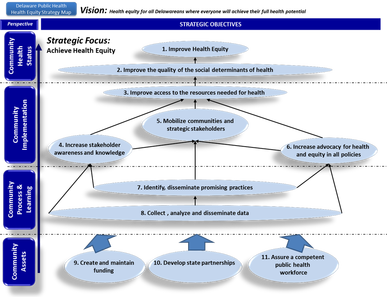

Figure 9: Delaware DPH Health Equity Strategy Map

Figure 9: Delaware DPH Health Equity Strategy Map

As described in the Delaware Division of Public Health [DPH] 2014-2017 Strategic Plan, DPH identifies health equity as one of its strategic priorities. Over the course of three years, DPH launched an organization- wide planning effort, where staff met to develop strategic, cross-cutting objectives, related activities, and performance measures that address health equity.

Consistent with a national effort to promote quality improvement in public health, DPH used a Balanced Scorecard strategy mapping process (Kaplan & Norton, 1992) to illustrate the division-wide performance management system (Fig. 9, shown left), which integrates a health equity strategy throughout. This DPH Equity Strategy Map complements the Division’s 2014-2017 Strategic Plan. Noted in Figure 9, DPH’s overall vision is “health equity for all Delawareans where everyone will achieve their full health potential.” Each objective is necessarily important for achieving this vision. The objectives of the strategy map are interrelated and those on the bottom of the map provide a foundation for those on the top.

This guide is intended to support the Community Implementation Objectives outlined in the center of the strategy map, but is grounded in an appreciation for efforts underway at each level which support the overall vision. This strategy reflects a shift from a framework of health disparities that largely focused on individual risk factors and disease-specific approaches to one that focuses more on communities, systems, and the underlying conditions that determine health. Still, DPH recognizes the need to continue to enhance many of its efforts in reducing individual risk factors and improving access to quality services. DPH’s approach parallels the integration of individual and population-based strategies recommended by the Secretary’s Advisory Committee for Healthy People 2020. Drawing upon the direction of the national strategies, DPH will use the Health Equity Guide for Public Health Practitioners and Partners to promote collaborative efforts that address health equity in the unique context of Delaware’s communities.

Consistent with a national effort to promote quality improvement in public health, DPH used a Balanced Scorecard strategy mapping process (Kaplan & Norton, 1992) to illustrate the division-wide performance management system (Fig. 9, shown left), which integrates a health equity strategy throughout. This DPH Equity Strategy Map complements the Division’s 2014-2017 Strategic Plan. Noted in Figure 9, DPH’s overall vision is “health equity for all Delawareans where everyone will achieve their full health potential.” Each objective is necessarily important for achieving this vision. The objectives of the strategy map are interrelated and those on the bottom of the map provide a foundation for those on the top.

This guide is intended to support the Community Implementation Objectives outlined in the center of the strategy map, but is grounded in an appreciation for efforts underway at each level which support the overall vision. This strategy reflects a shift from a framework of health disparities that largely focused on individual risk factors and disease-specific approaches to one that focuses more on communities, systems, and the underlying conditions that determine health. Still, DPH recognizes the need to continue to enhance many of its efforts in reducing individual risk factors and improving access to quality services. DPH’s approach parallels the integration of individual and population-based strategies recommended by the Secretary’s Advisory Committee for Healthy People 2020. Drawing upon the direction of the national strategies, DPH will use the Health Equity Guide for Public Health Practitioners and Partners to promote collaborative efforts that address health equity in the unique context of Delaware’s communities.

2. Delaware Health System Reform – Healthcare Innovation Plan

Delaware’s health care system is undergoing intense changes due to the passage of the ACA and related reform initiatives. Many local providers are already engaging in leadership and stewardship to advance health equity by identifying and implementing specific upstream interventions. These efforts can be expanded and enhanced. New initiatives grounded in the recommendations highlighted above can be developed in an environment conducive to such changes.

The Affordable Care Act created a Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI), housed within the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), to test innovative payment and service delivery models to reduce expenditures, while preserving or enhancing quality of care. Delaware was awarded funding from the CMMI State Innovation Model (SIM) initiative to test a plan for transforming the State’s health care system in ways that improve quality and reduce costs. Over $622 million in Model Test awards will support 11 states that are ready to implement their State Health Care Innovation Plans.

The Affordable Care Act created a Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI), housed within the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), to test innovative payment and service delivery models to reduce expenditures, while preserving or enhancing quality of care. Delaware was awarded funding from the CMMI State Innovation Model (SIM) initiative to test a plan for transforming the State’s health care system in ways that improve quality and reduce costs. Over $622 million in Model Test awards will support 11 states that are ready to implement their State Health Care Innovation Plans.

What is a State Health Care Innovation Plan? |

A State Health Care Innovation Plan is a fully developed proposal capable of creating statewide health transformation for the preponderance of care within a state. In addition, a State Health Care Innovation Plan describes a state’s strategy to utilize available regulatory and policy levers to accelerate transformation, such as plans to align quality measures, leverage the adoption and implementation of health information technology and health information exchange, and evaluate innovative efforts. CMS will work with Model Test states for four years.

|

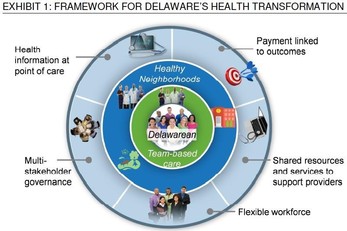

Delaware’s State Healthcare Innovation Plan was developed through an extensive and collaborative planning process and provides the basis for a subsequent application to CMMI for funding to implement the plan. The Delaware SIM Plan is organized around six work-streams—delivery system, population health, payment model, data and analytics, workforce, and policy— that contribute to achieving the Triple Aim of improving the health of Delawareans, improving the patient experience of care, and reducing health care costs.

The Delaware SIM Plan is grounded in an understanding of three major structural barriers to an effective health system. The first barrier is that the prevailing payment model incentivizes volume or quantity, rather than quality of care provided. Secondly, the health system in Delaware is fragmented, and coordination of care is often lacking. Finally, Delaware’s approach to population health does not integrate public health, health care delivery, and community resources in ways that promote health and an efficient use of resources. The framework illustrated in the figure to the right highlights the major components of Delaware’s strategy to overcome these barriers.

The Delaware SIM Plan’s focus on Healthy Neighborhoods as a way to transform Delaware’s approach to population health is viewed as a critical element to achieving the Triple Aim and leveraging resources for health equity. More specifically, Delaware’s Healthy Neighborhood program will provide resources for individual communities to identify and address community-specific health needs through targeted interventions. The program’s intent is to integrate public health and health care delivery on the local level, match existing community assets and resources with community-defined needs, and prioritize investments accordingly. In this way, Healthy Neighborhoods is consistent with the integrated approach recommended by the Secretary’s Advisory Committee for Healthy People 2020 and is supported by the Delaware Division of Public Health’s health equity strategy, both of which are described above.

Combined, increased focus on the SDOH and shifting toward more prevention-oriented and integrated systems of care create an important window of opportunity to advance health equity. Delaware appears poised to create a more effective, inclusive, and comprehensive health system that better addresses the entire continuum of health determinants, from the upstream social conditions to the downstream delivery of care. The potential benefits of such a system — for individuals, communities, businesses, and the state — are immense.

Combined, increased focus on the SDOH and shifting toward more prevention-oriented and integrated systems of care create an important window of opportunity to advance health equity. Delaware appears poised to create a more effective, inclusive, and comprehensive health system that better addresses the entire continuum of health determinants, from the upstream social conditions to the downstream delivery of care. The potential benefits of such a system — for individuals, communities, businesses, and the state — are immense.