Inside the Health Equity Toolbox -

|

|

Policy Oriented Strategies |

|

Policy-oriented strategies are generally thought to be among the most effective public health interventions because they have the potential to impact all of the residents in a given municipality, state, or nation. Furthermore, they often require the least individual effort in terms of behavior change due to broader changes in the environment.

For instance, regulating the nutritional content of school lunches is more effective than simply educating students about the nutritional content of their lunch options. As Dr. Thomas Frieden, Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), explains, this type of strategy makes individuals’ default choice the healthy choice (Frieden, 2010).

|

Policy-oriented strategies are particularly important in promoting health equity because they can create healthier living conditions and ameliorate inequities in the social determinants of health (e.g. housing conditions, educational attainment, etc.). It is apparent that many policy domains such as employment, housing, and education have an impact on health and health inequities. (See Figure to the Right) One could argue that virtually all public policy impacts health and therefore all public policy should be “healthy public policy” (Kemm, 2001).

|

Source: Dahlgren & Whitehead, 1991.

|

According to the World Health Organization (WHO, 1988), healthy public policy is characterized by an explicit concern for health and equity in all areas of policy and accountability for health impacts. Furthermore, the primary aim of healthy public policy is to create a supportive environment to enable people to lead healthy lives. Healthy public policy may also be described in terms of “health in all policies,” wherehealth becomes an explicit goal across different sectors and policy domains. Such policy approaches can facilitate place-based initiatives and support other efforts to promote community health, which were described in previous sections. Importantly, creating healthy public policy requires stakeholders to accurately predict and assess the health impacts of public policy. Finally, the policy process itself must adapt in ways that reflect increased community participation and empowerment as well as a multi-sectoral approach.

Health in All Policies

The Health in All Policies (HiAP) approach addresses the complexity of health inequities and improves population health by systematically incorporating health considerations into decision- making processes across sectors and at all government levels. HiAP emphasizes intersectoral collaboration among government agencies and shared planning and assessment between government, community-based organizations, and often businesses. While its primary purpose is to identify and improve how decisions in multiple sectors affect health, it can also identify ways in which better health achieves goals in other sectors. For instance, a HiAP approach supports goals such as job creation and economic stability, transportation access, environmental sustainability, educational attainment, and community safety because these are good for health. By identifying and working towards common goals, a HiAP approach can improve the efficiency of government agencies.

The HiAP approach is centered on the belief that population health issues must be approached through a number of methods, beyond those that target individual behaviors and the provision of health care services. In effect, it is grounded in the upstream parable described in the Health Equity Lens Section. More specifically, the HiAP approach recognizes that public policies outside of health care create the conditions upstream that can either protect individuals from falling into the river or potentially put them at greater risk for falling in. Furthermore, the HiAP approach reflects the understanding that individual behavior is largely determined by environmental conditions.

The HiAP approach and its underlying philosophy have taken hold in many parts of Western Europe, Australia, and New Zealand, but is relatively new in the United States. California is breaking new ground in this area, as described below.

The HiAP approach is centered on the belief that population health issues must be approached through a number of methods, beyond those that target individual behaviors and the provision of health care services. In effect, it is grounded in the upstream parable described in the Health Equity Lens Section. More specifically, the HiAP approach recognizes that public policies outside of health care create the conditions upstream that can either protect individuals from falling into the river or potentially put them at greater risk for falling in. Furthermore, the HiAP approach reflects the understanding that individual behavior is largely determined by environmental conditions.

The HiAP approach and its underlying philosophy have taken hold in many parts of Western Europe, Australia, and New Zealand, but is relatively new in the United States. California is breaking new ground in this area, as described below.

The Case of California

|

The California Health in All Policies Task Force was formed from a strategic community initiative under the leadership of former California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, who recognized that many departments and agencies had similar agendas related to health, childhood obesity, and climate change. The Task Force, established through a 2010 executive order, consists of representatives from 22 state agencies, including the Department of Education, Department of Finance, Department of Food and Agriculture, Department of Parks and Recreation, and Environmental Protection Agency. Details regarding the creation of the Task Force, the process used to identify priorities and build partnerships, and challenges, accomplishments and future plans can be found in Section 8 of Health in All Policies: A Guide for State and Local Governments by Rudolph, Caplan, Ben- Moshe, and Dillon (2013).

|

“HiAP, at its core, is an approach to addressing the social determinants of health that are the key drivers of health outcomes and health inequities” (Rudolph, Caplan, Ben-Moshe, & Dillon 2013). |

Recommended Resource

The information presented in this guide about HiAP draws heavily from Health in All Policies: A Guide for State and Local Governments by Rudolph, Caplan, Ben- Moshe, and Dillon (2013). We use the example of Delaware to highlight some of the most important elements of this approach for stakeholders. Readers are encouraged to refer to the original document for more detailed information and tools.

Health in All Policies: A Guide for State and Local Governments - Fostering Partnerships

The goal of HiAP is to make health an explicit consideration in seemingly unrelated policy decisions. Incorporating health into new policy fields requires collaboration with many different sectors. Agencies focused on food, agriculture, building, transportation, social, economic, or crime-control policies may become partners. The public health field has a long history of collaboration with different sectors, which must be continued and further developed to move forward with HiAP.

The most successful partnerships in HiAP are equally beneficial for all partners, which entails achieving specific goals for multiple organizations. This requires a great deal of negotiation and compromise and builds on the ideas of synergy, which were outlined in the community health strategies section. The following are additional principles for establishing partnerships with other policy sectors:

The most successful partnerships in HiAP are equally beneficial for all partners, which entails achieving specific goals for multiple organizations. This requires a great deal of negotiation and compromise and builds on the ideas of synergy, which were outlined in the community health strategies section. The following are additional principles for establishing partnerships with other policy sectors:

- Build trust. This is a difficult, but essential, step in forming any successful partnership. Be humble and open to other partners’ perspectives, goals, and values. Be sensitive to confidentiality between organizations by holding individual or sub-group meetings as well as larger group meetings. Hold your organization and your partners accountable for moving forward with the goals of the HiAP initiative.

- Model reciprocity. Partnerships involve a great deal of risk—most often requiring partners to risk two important assets, time, and resources—for the good of the partnership. Establish expectations and trust that partners will reciprocate. If possible, offer to help on a task that supports a partner’s efforts._ Ensure that credit is given where credit is due. Recognize that there will be misunderstandings with partners from different sectors and assume that your partners have good intentions towards advancing the HiAP initiative.

- Pursue mutuality. Ensure that partners have established shared values and are working towards mutually beneficial goals with no hidden agendas.

- Share information and ideas. Focus on highlighting ways for non-traditional partners to get involved in HiAP. Help others to understand how their work impacts health and how a healthy community can contribute to their efforts.

- Clarify language. Be extremely clear and make sure everyone understands one another. Avoid common public health jargon and abbreviations that may not be understood by partners from outside organizations.

Identifying Root CausesIdentifying root causes of public health issues may help to identify more indirect health policy correlations than initially imagined. For example, behavior is considered a proximate or downstream cause of poor health, whereas other factors in the environment which influence behavior are thought to be upstream because they represent root causes. Therefore, by conceptualizing the contributing factors, one can identify the root causes of any public health issue. Click the button below to access a more in-depth discussion of the root causes model.

HiAP in PracticeHiAP as an approach permeates all domains of policy making from housing and transportation to economic policy. However, because of the challenges associated with determining the various pathways through which these policies influence health, policy action has been incremental, yet limited. For a detailed discussion of HiAP in practice click the button below.

|

Engaging Community StakeholdersPartnerships across government agencies are critical to HiAP, but engaging other kinds of community stakeholders and residents is vital to ensure that efforts are aligned with community needs. Other kinds of stakeholders that may be important for promoting HiAP include civic groups, local coalitions, trade unions, faith-based organizations, school boards, and planning boards, to name a few. Community stakeholder engagement can be fostered through one-on-one discussions, community meetings, forums, and focus groups, as well as formal or informal advisory groups.

The HiAP Guide highlights the importance of meeting people “where they are” to encourage public participation, such as visiting regular meetings of church groups, parent groups, and other existing meetings. Similarly, social marketing strategies may be used to communicate simple, concise key messages to create awareness, common language, and community engagement. Additional outreach and engagement strategies discussed on the Strategies for Community Health page are directly applicable to HiAP. Readers are referred to the Community Toolbox for guidance in this area. |

Partnering to Achieve HiAP

|

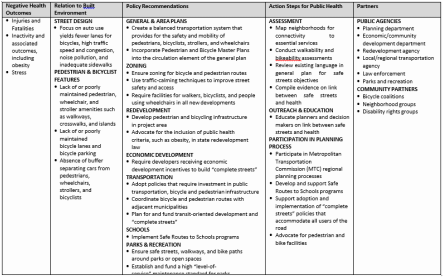

Given the strong relation between healthy neighborhoods and the built environment, experts have identified many areas where public health and planning agencies can partner to achieve common goals. The University of Delaware’s Institute for Public Administration developed a Toolkit for a Healthy Delaware. The toolkit offers information for local officials, public health practitioners, partners, and community leaders who want to develop policies and procedures with partners. Although the Toolkit for a Healthy Delaware has a specific focus for efforts that address the built environment, the strategies and tools within the toolkit can be generalized to begin important discussions regarding other policy issues. To access the toolkit, click here.

Additionally, the Healthy Planning Guide developed by the Bay Area Regional Health Inequities Initiative (BARHII) (n.d.), outlines policy recommendations, actions, and partners for community health risk factors, including alcohol and tobacco use, unsafe streets, polluted air, soil and water; and social isolation. A sample from the guide is included in the Figure below and readers are referred to the Healthy Planning Guide for additional examples and recommendations (click here). As shown in the figure, partnerships are critical to the success of HiAP efforts at the local, state, and national levels. Public health practitioners have an important leadership role to play in assessment, outreach, and education, as well as lending their expertise to the planning process for new policy initiatives or policy changes. |

Source: Bay Area Regional Health Inequities Initiative (BARHI), n.d

The BARHII guide identifies specific roles for public health practitioners in each of these key areas, depending on the nature of the issue being addressed. Engaging staff from other state agencies can be particularly important because of their ability to contribute expertise in areas that are outside of traditional public health knowledge: transportation, community development, law enforcement, and housing.

Other kinds of community partners can also inform the process with local knowledge and experience, fulfilling an advocacy role that is uncomfortable (and often restricted) for government employees. For a HiAP approach to make the most meaningful long-term impact on health equity, partners from multiple sectors need to join together and leverage their expertise, fill unique roles, and collaborate effectively to influence change. |

Health Impact Assessment (HIA) - A Tool for HiAP

|

Often the first step in undertaking a HiAP approach is to assess the potential health impacts of a given policy. This can be accomplished through the use of a Health Impact Assessment (HIA). As reported in a WHO Regional Office for Europe report, the most commonly cited definition explains that “HIA is a combination of procedures, methods and tools by which a policy, programme or project may be judged as to its potential effects on the health of a population, and the distribution of those effects within the population” (WHO, 2014; Diwan, 2000).

HIA often identifies methods to ensure positive health effects and can warn against practices that contribute to negative health impacts. By conducting HIA before policies of all types are developed and implemented, decision-makers and stakeholders can ensure the health of their constituents and those affected by policy decisions. Therefore, HIA provides insight into the consequences that policies, programs, and projects have on health. Just like HiAP takes into account policies that are not directly related to health, HIA is used to assess policies, programs and projects that are not seemingly related to health. Policies based in all sectors (including housing, zoning, education, agriculture, and transportation) indirectly affect the health of individuals and communities and therefore, it is vital to ensure that policies maximize positive, and minimize any negative, health impacts. |

“HIA seeks to assess the impact of actions (mostly from non- health sectors) on population health using a comprehensive model of health which includes social and environmental determinants” (WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2014). As defined by the National Research Council of the National Academies in their publication Improving Health in the United States: The Role of Health Impact Assessment, "HIA is a systematic process that uses an array of data sources and analytic methods and considers input from stakeholders to determine the potential effects of a proposed policy, plan, program, or project on the health of a population and the distribution of those effects within the population. HIA provides recommendations on monitoring and managing those effects." |

Our discussion of the HIA focuses on its as a method to determine the effects of policy on health and identify ways to improve the positive impacts of a given policy, while steering clear of adverse effects. It provides an in-depth description of the aspects of HIA, touches on the impact of HIA on health equity, and provides links to other comprehensive tools that facilitate its application. This section can be accessed by clicking on the button below.

Communicating for Healthy Public Policy

Creating the kinds of healthy public policies needed to advance health equity requires a significant shift in the way that most people understand health, health inequities, and the role of public policy in both. Building support for HiAP and for using HIAs requires that public health professionals, partners, and advocates reframe health from being something that is individual in nature and determined by personal choice, to something that is shaped by our environments and for which we have a collective responsibility to improve. These approaches to understanding health move from an individual and behavioral frame to an environmental frame. As discussed in the HiAP Guide for State and Local Governments (Rudolph, Caplan, Ben- Moshe, & Dillon, 2013), it is important to communicate this environmental frame early and often. A prevailing misconception is that the best way to improve health is through access to health care and healthier individual choices. Therefore, it is critical to communicate effectively how the places in which we live, learn, work, and play affect our health. Once this environmental frame is understood, it is easier to convince people about the need for improving their environment to improve health. And this comprehension is necessary for a HiAP approach.

In addition to presenting an environmental frame, it is important to identify and then use commonly held values when communicating with stakeholders. This can be difficult for public health professionals or others who may be uncomfortable in moving away from statistics and research often used to make the case. However, values and emotion are what move people, and these need to be part of the conversation. In promoting a shift to an environmental frame and HiAP, the consistency and credibility of the message is also important. Additionally,communication strategies are most effective when they are audience-specific. Knowing the audience and their starting point can help craft tailored messages. Similarly, having a messenger who resembles or relates to the audience may influence the effectiveness of the messages because people tend to be more receptive to people like them. Some pay more attention to messages coming from persons whom they perceive are respected sources (Rudolph, Caplan, Ben-Moshe & Dillon, 2013). Finally, it is critical that communication strategies include a focus on solutions. As explained by the authors of the HiAP Guide for State and Local Governments:

“People are more inclined to act when they feel they can do something to solve a problem. But often public health professionals spend more time talking about the problem than the solution, leaving their audience feeling hopeless or overwhelmed. To more effectively inspire action we need to reverse that ratio and talk more about the solution than the problem. For example: “Increased access to healthy food will improve nutrition and contribute to reducing rates of childhood overweight and adult diabetes. Ensuring that everyone has access to healthy, affordable food can be complicated, but there are meaningful steps we can take right now. That’s why we’re asking [specific person/agency/ organization] to support the Healthy Food Financing Initiative to increase access to healthy food in our neighborhood.” (Rudolph, Caplan, Ben-Moshe & Dillon, 2013, p. 105).

The HiAP Guide for State and Local Governments includes a detailed discussion of communication with several recommendations and sample messages. The authors include sample responses to commonly asked questions and offer a number of additional resources. The authors explain that the critical components to an effective message are:

- Make sure to present the environmental frame first.

- State your values (e.g. health, equity, community, etc.).

- State the solution clearly, and be sure that the solution gets at least as much, if not more, attention than the problem.

“To make the case for healthy public policy most effectively, it is important to offer an alternative to the default frame of personal responsibility” (Rudolphe, Caplan, Ben-Moshe, & Dillon, 2013).